A Pretty Village with an Ancient History

Ban Chiang is a picture postcard Thai Village with a remarkable history as it sits on the remains of Thailand’s first Bronze Age Settlement. Further, the settlement was at the forefront of cultural, social and technological evolution in the region. It was here where the first farms were laid, where the first metals were forged and from where a vibrant, sophisticated culture spread across the whole of South-East Asia.

The evidence for this all comes from amazingly well-preserved artifacts which have survived in jaw-dropping numbers. These include pottery, bronze spears, bronze jewellery as well as glass and iron objects. The most recognized of these are the iron age red-on-buff painted ceramic pots which are now an iconic symbol of the Udon Thani province.

To visit Ban Chiang, its excellent museum and archaeological sites is to step back in time and become a witness to human evolution. Ban Chiang was continually occupied for 900 years, a period that straddled the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages. Here you can see a complete record of how we evolved into who we are today.

The First Bronze Age Settlement – What It Was Like

The settlement would have been about 300 people at its largest. Both hunters and farmers, they would have raised pigs, cows and buffaloes for food as well as labour. The total areas was about 30 Rai (12 acres) with much of the land given to rice cultivation. They would have also have eaten fish, chickens and civets. Certainly, dogs were reared and raised in their households chiefly for hunting though in hard times would have themselves become dinner.

Archaeologists have identified several periods of development described in the three buckets of Early, Middle and Late Periods. It is believed that bronzemaking was already taking place in the Early Period. Over time, they developed increasingly sophisticated production methods especially in varying the percentage of tin, the heating temperature as well as the cooling methods used. The resultant bronze was a beautiful colour and neither brittle nor prone to breaking.

The bronze making process involved using earthen crucibles for melting and pouring the bronze into bivalve stone moulds. The resultant bronze piece would then have been beaten to increase the toughness before having decorative details added.

At the same time that Ban Chiang was settled, other settlements were established at Non Nok Tha, Ban Lum Khao and Ban Na Di each of roughly the same size and design. This would have made an interconnected network of settlements across Isan.

Wealth and Influence That Spread Across an Entire Region

With the production of metals came wealth and prominence. Metals are easier to shape than wood or bone and much longer-lasting. So with this knowledge, they would have been more efficient plus able to increase their wealth through trade. There is evidence that the items made here were traded with villages in both Vietnam and India. And with prosperity came social, cultural and technological evolution that further enhanced both wealth and influence. Over time, the settlement became the preeminent village in the region.

What is also interesting though to anthropologists and archaeologists is that this flourishing and evolution took place without the normally associated parallel development of social hierarchies, elites and military organisations. In fact, no found skeleton has shown any sign of injury associated with internal or external conflict as is the norm in the rest of the world.

Generally, it seems, that people were healthy, lived longer than people in other areas, had fewer disease and saw a lower infant mortality. For 900 years, Ban Chiang was a peaceful agrarian community that thrived and prospered whilst continually evolving technologically and artistically.

The Ritual Burials That Helped Preserve So Many Artifacts

The original settlers at Ban Chiang lived at a time before Buddhism and their belief system would have been grounded in the spirit world. This led to highly ritualized burials in ‘burial pits’ to which were added many of the person’s earthly belongings. It is these burial pits that so perfectly preserved the ceramic pots as well as the bronze and iron items that we have today.

Typically, a body was buried in a pit near their dwelling rather than in a separate burial area. This is known as ‘residential burial’ and it is hypothesised that this for them to keep a connection to their deceased relatives.

The body would have been covered with a shroud or a cloth. Around the body were placed multiple pots, some whole and some smashed. The deceased’s possessions, such as axes, spearheads, were also buried though interestingly most were bent out of shape prior to the burial. In fact, one of the most common finds are spearheads with the tip bent forward. It is assumed that this was to the ‘kill’ the item so it could be taken to the next world. Necklaces, bracelets, waist hoops and other jewellery were placed on the body as they would have worn in daily use.

Infants were placed in wide-mouth pots with inscriptions on the sides and a lid. This was common not just to Ban Chiang but the wider region as well.

The Burial Ritual did evolve over time. For example, Middle Period pottery was almost always smashed before being placed the burial pit whilst Late Period pottery was always placed whole. This is why so many red-on-buff pots survived as they are extensively from the late period.

The Founding Of Modern Ban Chiang and the Discovery of the Pottery

After 900 years of continued occupation, Ban Chiang was abandoned around 500BCE potentially tdue to climate change making the land drier and unsuitable for farming. After that time the settlement lay undisturbed and unnoticed for a further 1,300 years slowly building up a protective layer of mud and dirt that helped preserve the remains.

About 200 years ago, the Tai Phuan people left their village Chiang Kwang in what is now Laos and crossed the Mekong River into Isan. The Tai Phuan are an ethnic group that first migrated from South-East China to Laos before settling in Ban Chiang.

When they arrived at Ban Chiang, the raised mound over the ancient settlement seemed a perfect location to build their homes and farms. Though they would have been unaware of what lay beneath, the raised area offered natural protection against floods. Near the mound, there were two conjoining rivers and large low-lying plains beyond. That would have indicated to the Tai Phuan these were also good, fertile farming lands.

As this community of Tai Phuan grew and developed they began digging into the earth below to build foundations for their houses and farm buildings. This started to reveal fragments of pottery and other remains. The most significant of these were three whole and intact painted pots found by Banlu Montripitak, the village doctor, when digging foundations for his house in 1957.

These three pots were displayed in the Ban Chiang Elementary School which began collecting all further found pottery. Samples were also sent to Charoen Polteja at the Fine Arts Department’s offices in Khon Keng sparking the first professional archaeologist interest.

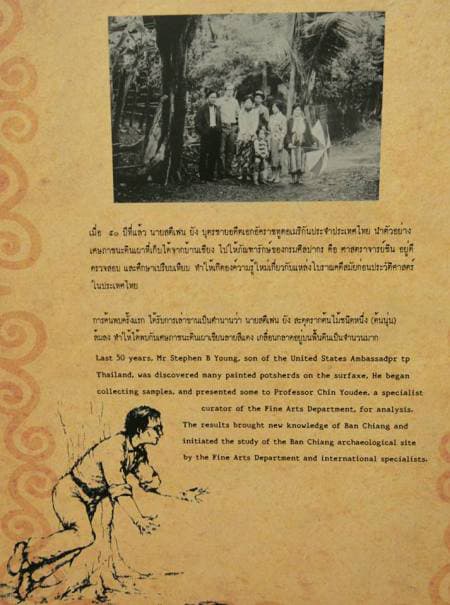

How Steve Young Sparked Global Interest in Ban Chiang

The significance and age of the these early discoveries were little understood at first. It took an accidental fall by a visiting American University student to bring Ban Chiang to international attention.

Steve Young was the son of the then US Ambassador to Thailand. He travelled to Ban Chiang in 1966 to work on his thesis as part of his political course at Harvard University. The story goes that, whilst walking with two colleagues, he tripped on a root of a kapok tree and fell face first onto a dirt path.

Underneath him were the rims of pots which had been left exposed by recent rains. He quickly realized that the techniques used to make the pots were very rudimentary, hence suggesting their age, but that the designs were unique. Also, he discovered that the area around him was littered with so many pots and that he had stumbled on something uniquely special.

He brought samples of the pots back to Bangkok giving some to Princess Phanthip Chumbote for the Suan Pakkad Palace Museum. Further samples went to Chin Yu Di of the Thai Government’s Fine Arts Department. Later samples were then sent to University of Pennsylvania for dating bringing Ban Chiang to international attention and launching the first formal excavations.

The First Excavations

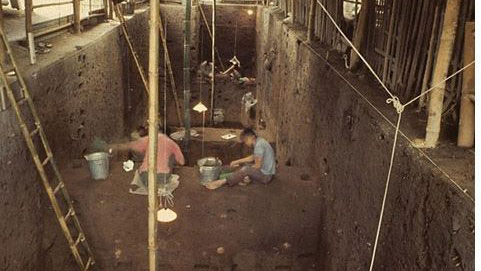

The first excavations of the site took place the following year in 1967. This revealed burial pits with several skeletons, pottery and bronze burial gifts. The earliest graves found contained no bronze items suggesting the settlers were from the Neolithic Period (third period of the stone age). The latest graves were dated to iron age showing the extended period that the site was occupied.

The second major excavations took place between 1974-1975 conducted by the American Archaeologist Chester Gorman and the local Pisit Charoenwongsa. This excavation alone uncovered 123 skeletons, 200 perfectly in-tact pots, over 11m ceramics shards as well as evidence that bronze forging had actually taken place at the site.

Ban Chiang Controversy: Dating of the Site

It is still debated amongst archaeologist as to when Ban Chiang was first settled. This is of interest as it provides vital clues as to where the discovery to make tin, copper and bronze first took place and how it then spread across the world.

Chester and Pisit, using thermoluminescence techniques on remains from their 1974-1975 excavations, produced dates of the first bronze production taking place around 3,600 BCE and iron production around 1600 BCE. This was sensational at the time as it would have upended the prevalent understanding of prehistoric history.

If true, it would have meant that Ban Chiang was the oldest Bronze Age settlement in the world and not just Thailand. The implication would have been that the discovery of metal manufacturing took place here independently of elsewhere and that this knowledge would have spread from here to the rest of the world. When Chester and Pisit announced their findings it launched Ban Chiang instantly into the global spotlight.

As exciting a claim as it was, subsequent dating by Joyce White, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, produced a much later date. Joyce used a bigger sample of materials, chiefly rice fragments, and different dating techniques to arrive at a date of 2,000BCE – 1,800BCE for the start of the Bronze Age at Ban Chiang. This was still sensational as it would imply that metal manufacturing techniques would have arrived complete from Mesopotamia and at a much earlier time than was previously thought possible.

A third dating, however, was provided by Charles Higham who was the Research Professor at the University of Otago, New Zealand. Higham had been involved in the 1974-1975 excavations as well as the nearby Bronze Age settlements at Ban Na Di and Ban Non Wa. He based his dating using animal bones from several bronze age sites in Isan to conclude that Ban Chiang was settled around 1,500BCE with Bronze production starting around 1,000BCE. This would imply that bronze making knowledge was transferred through South West China during the Shang Dynasty with some refinement of the manufacturing process taking place locally.

Whilst the debate continues on dates, what is not contentious is the importance of Ban Chiang as an archaeological site. What was found here changed perceptions of the Isan region in the eyes of historians. Previously considered a backwater of little interest, it was now realised that this area was actually a fountain of culture, arts and development that occurred independently of China or India.

More Controversy: Whole Theft of Artifacts

The initial interest in Ban Chiang also birthed an industrial-scale theft of antiquities out of the settlement peaking in the early 1970s. Whist the modern occupants had been aware of the pottery underneath their homes, it was not recognized as having any monetary value. There was after all no-one wanting to buy them.

That changed with the announcement that Ban Chiang might be the earliest Bronze Age Settlement globally in the 1970s. Suddenly there was a rush of antiquity traders, curious tourists looking for mementoes, and busloads of US Soldiers from the nearby airbase at Udon Thani. To satisfy this demand, residents would dig shafts down to the required height and then build tunnels out. Specifically they were looking for the red-on-buff iron age pots.

Whilst the sums of money was never huge, it was enough to improve the fortunes of the Ban Chiang residents who were able to spend more on medical care, their children’s education as well as improving their properties. Even today Ban Chiang has a certain polish to it lacking in other villages in the area.

It is believed that some 40,000 pots plus other items made their way over the US with many being sold to museums. Today almost every US museum that collects Asian artifacts has multiple Ban Chiang potteries and Bronzes. All of this is illegal since Thailand passed antiquities legislation in 1961.

There has been a concerted effort to repatriate artifacts back to Thailand. For example, in 2008 three US federal agencies including the FBI arrested several antiquity dealers as well as raiding four California museums: the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Bowers Museum of Art in Santa Ana, the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena and the Mingei International Museum in San Diego. In the affidavits filed to obtain search warrants, the agents laid the groundwork for a legal argument that virtually all Ban Chiang material in the United States is stolen property. This gave hope and inspired more efforts to bring more artifacts back to Thailand.

For Example in 2015, the Kanjanapisek National Museum in Pathum Thani hosted an exhibition of over 500 items that had been returned earlier that year. The trickle of items coming back is slow but continuous meaning that every year more and more Ban Chiang artifacts are where they belong: in Ban Chiang.

Touring Ban Chiang

Ban Chiang is itself a delightful village and worthy of a full, or near full day, of visiting the sites, local markets and soaking up the relaxed and friendly atmosphere. There are also several places that serve excellent Isan food and it would be a wasted journey not to browse the shops selling replica pottery.

Everything you will want to see is in close proximity but you can hire bicycles from a store next to the museum for about 10 baht an hour. This is a delightful way to not just to move from site to site but also to explore the village, markets, shops and surrounding nature.

Ban Chiang National Museum is a surprisingly excellent museum and credit to all those, including the Smithsonian Institution, who developed it. It is well signposted around the village and easy to find even without GPS. Here you will find on display a wealth of artifacts and especially the pottery. It is easy to see how the artistry developed over the centuries evolving into the now-famous red spiral patterns. The museum doesn’t just focus on Ban Chiang but has items on display from over 120 archaeological excavations across Udon Thani, Nong Khai and Sakhon Nakhon giving a broad perspective.

The museum also has a section recounting the story behind the first discovery, initial excavations and ongoing research. Another section documents the illegal trade in ceramics and how it enriched the village whilst a further section focuses on the Tai Phuan people and their arrival in the 18th century. Entrance is 150 baht for foreigners and 30 baht for locals. It is closed Mondays.

It is worth noting that archaeologists are constantly revising dates for the settlement though the museum isn’t as quick, understandably of course, in updating the dates on the information boards. Hence there are discrepancies between what is articulated elsewhere and in the museum itself.

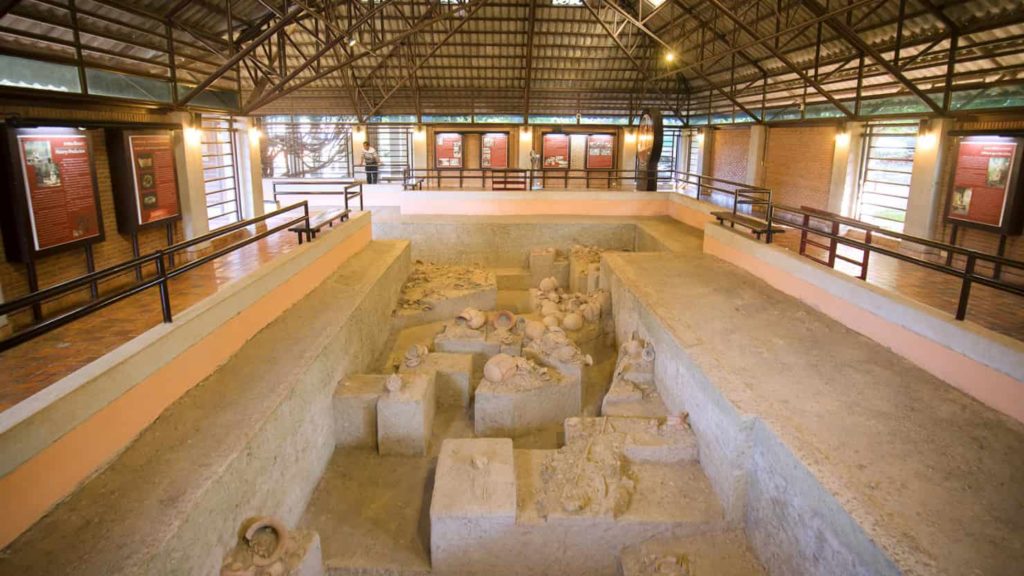

Wat Pho Si Nai Burial Site is a short 750m walk from the museum. This is the largest burial ground to have been excavated and the only one to have been left open. It sits under a raised roof with good information boards on one side. There are 52 skeletons here along with much pottery though it is worth noting that after a flood the real skeletons were moved to the museum and replaced by resin replicas. The site is maintained by the monks at Wat Pho Si Nai, which is next door. Both the temple and excavation pit are free to visit.

The Tai Phunan people are known for their excellent handwoven textiles and this practice continues today in the village. Mainly they produce indigo-blue striped and patterned pakama, a short sarong worn by men, and a pasin tin jok, a longer women’s skirt. You can also find scarves, shirts and jackets. Whilst these are plentiful to buy, you can visit the Sor Hong Daeng Ban Chiang Weaving Group and watch the weaving processing action. You can also have a go at dyeing your own scarf or handkerchief!

Similarly you can learn traditional pottery skills and make your own replica pot at Ban Chiang Pottery Group or learn traditional Tai Phunan basket weaving.

Getting to Ban Chiang

Ban Chiang is 50km East of Udon Thani and 105km Southeast of Nong Khai. If you are driving yourself, it is a relatively easy and picturesque drive. If coming from Udon Thani head east on Highway 22. About 6km out from Ban Chiang there is a left fork onto Route 2003. The Junction is heavily signed posted and there is a collection of oversized reproduction red-on-buff pots. If coming from Nong Khai, head south on Route 2 before going clockwise around the Udon Thani ring road and connecting to Route 22.

If coming by taxi be prepared to pay between 1,500-2,000 baht for the round trip from Udon Thani.

There are no direct buses to Ban Chiang from Udon Thani but buses do run to Nakhon Phanom and Udon Sakhon. You can ask to be dropped off at the junction to Ban Chiang or at the market in Nong Han. Nong Han is a little further but it is easier to find a songthaew or a tuk-tuk to take you the final stretch. Expect to pay around 500 baht for the round trip.

There are several very friendly guest houses most offering excellent Isan food.

Combine With a Trip to…

Ban Chiang sits to the East of Udon Thani long two other worthwhile sites that can be combined into a single day trip though does make for a long day”

Wat Pa Dong Ra (Lotus Flower Temple)

The easiest order to do these three would be start at Red Lotus Lake in the early morning. Then travel to Ban Chiang before moving on to Wat Pa Dong Ra.